You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘tutu’ tag.

Tag Archive

The Tutu: Costume Extraordinaire

May 8, 2013 in dance | Tags: ballerina, ballet, barre, dance, dancer, dancing, diablo, exercise, pointe, san francisco, tutu, walnut creek | Leave a comment

makes them pretty vogueish. They’re everywhere, from the catwalks of Paris to the bottoms of babes–in fact the name tutu is rumored to be French babytalk for backside. But while they may lend inspiration to fashion designers, artists, and little girls masquerading as princesses, they still owe their allegience entirely to ballet. In fact, I think their essential femininity and beauty come from the very fact that their design evolved in response to the elegant steps and body of the ballerina herself.

makes them pretty vogueish. They’re everywhere, from the catwalks of Paris to the bottoms of babes–in fact the name tutu is rumored to be French babytalk for backside. But while they may lend inspiration to fashion designers, artists, and little girls masquerading as princesses, they still owe their allegience entirely to ballet. In fact, I think their essential femininity and beauty come from the very fact that their design evolved in response to the elegant steps and body of the ballerina herself. Since then, the tutu’s length and shape have been modified many times over with the driving force behind the shorter hemlines being the audience’s desire to see more legwork. The Degas tutu (named for the artist who painted them) is a bell shaped, knee length version of the romantic tutu. The pancake and platter tutus are the shortest varieties, both being constructed with wire hoops allowing them to stick straight out from the body– the platter tutu is the flatter on top than the pancake. The powderpuff tutu is a wireless and softer version of the pancake, designed expressly for the ballets of George Balanchine.

Since then, the tutu’s length and shape have been modified many times over with the driving force behind the shorter hemlines being the audience’s desire to see more legwork. The Degas tutu (named for the artist who painted them) is a bell shaped, knee length version of the romantic tutu. The pancake and platter tutus are the shortest varieties, both being constructed with wire hoops allowing them to stick straight out from the body– the platter tutu is the flatter on top than the pancake. The powderpuff tutu is a wireless and softer version of the pancake, designed expressly for the ballets of George Balanchine.

Balanchine worked closely with legendary tutu designer Barbara Karinska, a fellow Russian emigrée, to create a tutu that would have the fullness of the pancake without the distracting reverberating movements created by the wire hoops. Forty dancers appeared together on stage wearing Karinska’s powderpuff prototype for Symphony in C. Balanchine said of Karinska: ”I attribute to her fifty percent of the success of my ballets to those that she has dressed”–pretty remarkable considering she dressed seventy-five of his ballets.

Tutu design and construction are no simple matter. Countless hours of work are required to create the ethereal costumes that are an essential component of ballet’s magic. And the creation of the tutu must appear as effortless as the creation of the dance, the two blending together fluidly as one. The tutu’s bodice must fit a ballerina to absolute perfection. If it is too tight, it will impede movement and breathing; if it is too loose, it will move around her body, instead of with it, above all when she pirouettes. The decorations used to adorn it, whether jewels or feathers, also need to be strategically placed, especially if the tutu is for a dance in which the ballerina will be lifted by a male dancer.

proved irresistible to fashion designers. To honor Coco Chanel’s former costume designs for the Ballet Russes, Karl Lagerfeld (current creative director of the house of Chanel) recently designed a tutu for the English National Ballet’s production of the Ballet Russe’s own “Dying Swan”, performed by ballerina Elena Glurdjidze. More than one hundred hours of work went into the dress, many of those taking place solely at the studio of Chanel’s “plumassier”, or feather specialist. To a non dancer like me, the result was stunning, however it met with mixed reviews. One critic claimed “Lagerfeld’s tutu was conceived with cavalier disregard for the ballerina’s working body–the line of the neck broken by an egregious fluffy ruff, the waistline broken by a too-high skirt.”

proved irresistible to fashion designers. To honor Coco Chanel’s former costume designs for the Ballet Russes, Karl Lagerfeld (current creative director of the house of Chanel) recently designed a tutu for the English National Ballet’s production of the Ballet Russe’s own “Dying Swan”, performed by ballerina Elena Glurdjidze. More than one hundred hours of work went into the dress, many of those taking place solely at the studio of Chanel’s “plumassier”, or feather specialist. To a non dancer like me, the result was stunning, however it met with mixed reviews. One critic claimed “Lagerfeld’s tutu was conceived with cavalier disregard for the ballerina’s working body–the line of the neck broken by an egregious fluffy ruff, the waistline broken by a too-high skirt.” Just last year another fashion legend,Valentino, designed costumes for the New York City Ballet’s “Bal de Couture”, and also received less than glowing reviews. Without a real understanding of balletic movement, I can imagine it would be extremely difficult to successfully bridge the two arts of fashion and ballet. There’s a big difference between a still dress on a hanger and a moving dress on a ballerina.

Just last year another fashion legend,Valentino, designed costumes for the New York City Ballet’s “Bal de Couture”, and also received less than glowing reviews. Without a real understanding of balletic movement, I can imagine it would be extremely difficult to successfully bridge the two arts of fashion and ballet. There’s a big difference between a still dress on a hanger and a moving dress on a ballerina.Going En Pointe: An Interview With Diablo Ballet Dancer Jennifer Friel Dille

April 2, 2013 in dance | Tags: "diablo ballet", ballerina, ballet, california, choreography, dance, dancer, dancing, diablo, movement, performer, pointe, pointe shoes, san francisco, social media, tutu, walnut creek | 2 comments

By Liesl Ferreira

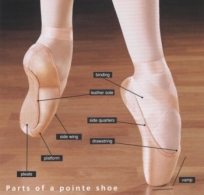

Just an image of pointe shoes evokes the elegance and grace of ballet. A  dancer’s first pair is a rite of passage, from little girl to serious ballerina. But the risk of injuries to her feet can be serious as well, and increases if pointe work is started too young, before she is ready either physically or technically.

dancer’s first pair is a rite of passage, from little girl to serious ballerina. But the risk of injuries to her feet can be serious as well, and increases if pointe work is started too young, before she is ready either physically or technically.

As someone whose feet throb after five minutes in heels, I became fascinated with the feet beneath the pink satin. I interviewed Diablo Ballet dancer Jennifer Friel Dille about her experience en pointe. Her eloquent answers to my sometimes silly questions reminded me of what I had forgotten while naively focusing on the frightening aspect of foot injuries: there is an element of sacrifice to all artistic pursuits. Ballerinas dance through their pain driven by passion. Personally, I’m grateful they do.

Q: How old were you when you got your first pair of pointe shoes?

A: I was nine years old when I got my first pair of pointe shoes, which is extremely young. I was in a dance class with girls that were a year or two older than me but it was still pretty young to be dancing en pointe.

Q: How did beginning pointe work change how you felt about yourself as a dancer (or even as a person)?

A: When I began pointe work I was really excited about advancement and growing up. I’m sure it wasn’t pretty at the time, but it felt like I was on the path to becoming a ballerina.

Q: I have read about certain criteria teachers use to determine pointe readiness: age, strength, technique, discipline, etc. How did your teacher determine you were ready for your first pair of pointe shoes? Did you feel ready yourself when you started dancing in them? Did you experience pain initially, or was the transition smooth?

A: My teacher determined pointe readiness by strength, flexibility, experience, level in the school, and the number of classes attended weekly. As I mentioned, I was pretty young but I certainly thought I was ready. I was SO EXCITED to get my first pair of pointe shoes. I definitely wore them around the house and did relevé’s in the kitchen. I think that I did all of the things they tell you NOT to do before you start taking pointe class. I did feel a little discomfort when I got a blister or bruised toenail, but overall the transition was pretty smooth. I don’t think that pointe work is inherently painful. I’ve always loved working en pointe.

Jennie Somogy, 29, principal dancer with the New York City Ballet. “I’ve been a professional dancer for 13 years. I was on pointe at 8 years old, just one year after I started dancing, because my ballet teacher thought I was strong for my age. She told me never to pamper my feet. A lot of dancers tape their toes, but she said I shouldn’t: If I was ever without tape, I wouldn’t be able to dance.”

Photo Credit: Robert Maxwell – From Marie Claire 2010

Q: It was easy to find information on the many risks of starting pointe at a young age, but what are some benefits to beginning early? (As an outsider, it would seem like all young dancers should wait as long as possible to begin pointe work to ensure the long term health of their feet, yet this does not always seem to happen. I am wondering why anyone would ever rush into it.)

A: I think one of the benefits of starting early is gaining ankle and foot strength. Also, taking classes en pointe is a completely different animal than taking class in ballet slippers–turns are different, balance is more difficult because the platform of the shoe makes an unstable surface even when standing. Jumping in pointe shoes is difficult because you have to push off the floor harder than in ballet slippers. It makes sense to get used to the difficulty of working in pointe shoes if you are going to be performing in pointe shoes instead of ballet slippers.

Q: Do you think if the physical sacrifices dancers make for their art were more publicized, it would boost interest in ballet? Or might it detract from the magic?

A: That is a difficult question! I think that many people already recognize the sacrifices dancers make. There are so many movies and TV programs that show the rough side of the ballet world. I often get questions from non-dancers about injuries and eating disorders and pointe work. In that case, I think we are like most any other high level athletes. We work hard in a physical way and demand a lot of our bodies. But the magic of the art of dance is what makes ballet different. I think that we need both. I would love it if people recognized the hard physical work that dancers do but also realize that making our movement look effortless is magical and separates us as an art.

Q: Are there lasting effects to a dancer’s feet after her career is over? Do you worry about this?

A: Every dancer’s experience will be slightly different. Some foot damage may start as a genetic abnormality, but is exacerbated by pointe work (or ballet in general)–bunions may be such an example. I know dancers, who have had corrective surgery for foot injuries after they stop dancing. I have already come to terms with the fact that my feet will never be pretty. I have some pretty crazy calluses. Personally, though, I worry just as much about my back or my hips or my knees as I do about my feet.

Q: What kind of shoes do you wear when you are not dancing? (I cannot imagine you would ever want to wear high heels!)

A: Oh boy. When I’m traveling to or from the studio I usually wear supportive sneakers. I like to wear flip flops around the apartment. But if I’m getting dressed up to go out, I wear high heels. Guilty as charged. 🙂

Q: From some of the photos I’ve seen of dancers’ feet, I would guess that a ballerina who spends a great deal of time en pointe would have feet that were hardened and accustomed to being in that particular shape. And therefore, it might be difficult for her to transition easily from pointe to demi pointe work. Is this at all true? What portion of a typical day of training do you spend en pointe? What about when you first started pointe work as a girl?

A: What an interesting question. In my personal experience, these days professional dancers have to perform in so many different kinds of ballets (in ballet slippers, in bare feet, in socks, in pointe shoes). You have to be able to transition back and forth. For instance, in Diablo Ballet’s last performance. I performed in pointe shoes for La Covacha and in socks for Flight of the Dodo. On a more basic level, when dancing en pointe you still have to work through your demi pointe anyway so the transition for a professional dancer isn’t too difficult.

How long I spend en pointe each day depends on which ballets I’m cast in. If I’m rehearsing for a ballet that requires pointe shoes all day, I could be in shoes for 5 hours or so. If I’m performing I could be in and out of pointe shoes for 8 hours.

When I first started pointe work I had two one hour pointe classes a week. I also had a great teacher in my teenage years that made us wear “soft” pointe shoes for every ballet class. In her class our feet got used to the platform and the shaping of the feet in the shoes without going onto pointe in class.

Q: Are there certain ballets that are notoriously hard on the feet?

Members of the Mariinsky Ballet perform in Swan Lake. Photo: Courtesy Mariinsky Ballet and Orchestra

A: I’m not sure how my fellow dancers would answer this question, but in my memory, performing in the corps de ballet of the long classical ballets was hardest (Swan Lake and Giselle). In those ballets, the corps dances very hard and in complete unison, then they stop and stand completely still for entire minutes at a time. Imagine jumping and hopping and pointing your feet as hard as possible and then standing without moving. The cramping was unbelievable.

Otherwise, I think it’s more personal. I remember some ballets being hard on my feet because I had a bruised toenail, a painful corn, or a terrible blister. That was circumstance rather than the ballet itself.

Q: It has been said that ballerinas have a love/hate relationship to their pointe shoes. What  do you love about your pointe shoes? And conversely, what do you hate about them (if anything)?

do you love about your pointe shoes? And conversely, what do you hate about them (if anything)?

A: I do have a love/hate relationship with my pointe shoes. I love to dance en pointe. It allows a certain freedom that dancing on demi-pointe doesn’t. I love turning on a good pair of pointe shoes. But it is a lifelong quest to find the perfect pair of shoes. Pointe shoes are handmade and each one is a little different. Most of us have a favorite “maker” for our shoes. But even shoes made by the same person can vary quite a bit. It doesn’t take much to throw you off balance when you are on the narrow tip of your toes. Sometimes favorite makers pass away, or stop making shoes and the search starts all over again. Good shoes can make a show go well or make a show feel shaky or “off”. It can be frustrating but I still love dancing in pointe shoes!

Click here to meet Diablo Ballet’s Jennifer Friel Dille. Jennifer will be performing at the April 12th and 13th Hillbarn Theatre performances and May 3rd & 4th Inside the Dancer’s Studio. Click here for information.

Liesl Ferreira is a native of the Bay Area who developed a passionate interest in the arts while living in Paris for more than a decade. She believes that the arts belong everywhere, in every life, and that the ability to express our humanity, or be touched by an expression of this humanity, is inherent in us all. She devotes her life to her family, photography, and Iyengar Yoga. Liesl is a wonderful volunteer with Diablo Ballet.